By Heidi Hardman-Welsh

Friends of Legends

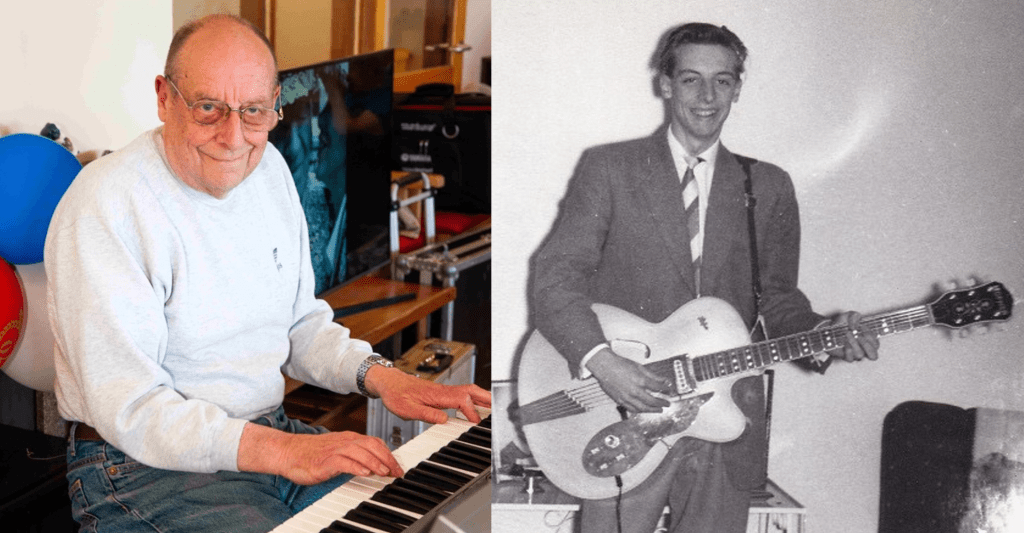

In the quiet of the Scottish Highlands, far from Liverpool’s bustle, Peter Hindley, 84, reflects on a childhood once intertwined with one of the most famous musicians the world has ever known. As a boy at Quarry Bank Grammar, Peter was classmates with John Lennon, not the global icon, but a restless teenager who, by his own admission, was “terrible” in school.

“He was always in trouble,” Peter laughed. “He couldn’t concentrate because he was messing around all the time, flicking pellets at you, making a nuisance of himself. I think that’s why my marks were so low. He never got blamed for anything. He always got other people into trouble.”

Yet despite the mischief, Lennon was popular. “He could do things and get away with it,” he recalled. “He was bigger and stockier than the rest of us. People liked him for that.”

Even Peter’s mother was wary of the boy. “She said to me, ‘Don’t get involved with him. He’s a nasty bit of work. Just get on with your exams and leave him be.’ She had him weighed up fairly well.”

What nobody foresaw, not even Lennon’s closest friends, was how music would transform him. Both Peter and John taught themselves guitar.

He said: “I had Bert Weedon’s guitar tutor book, but I never learnt to read music. I just messed around until I got it right. John was the same. We started off with two chords, then he’d find another one, and we’d all try that. He was always one step ahead of us.”

It was at John’s best friend Pete Shotton’s house that those early experiments began to sound like something more. “We’d play Lonnie Donegan, Bill Haley, Jerry Lee Lewis. We all had guitars, except Pete, and we’d bash our way through the songs.

“Only later did I realise what I was hearing was the beginning of something different. John never stuck to musical theory, he experimented. Some things worked, some didn’t, but that’s why his songs with Paul [McCartney] ended up sounding so fresh.”

Peter himself kept music close even after leaving Liverpool in 1958. He joined the RAF and played with bands across Germany and Holland. “We travelled all over the camps and the American bases,” he said. “It gave me a taste of it, and we had the usual following of groupies, but I couldn’t have done it full time.”

His prized instrument at the time was a Höfner Galaxie, “a poor man’s Fender,” though today he treasures a blonde Höfner President, bought in memory of the one he owned years ago.

Though he watched Lennon rise to global stardom, Peter never wished it was him on the stage. “When I saw him on TV with The Beatles, I just thought, I used to play guitar with that lad. Look at him now.”

“I never thought he’d make something of himself, to be honest, because he was too rough, you know. Actually, it was a bit of a shock when I found out he was getting famous, although I was very pleased for him, obviously. But I wouldn’t swap the life I’ve had, it’s been brilliant.”

Still, his memories remain rooted in the small moments: “I always look back with fondness,” he said. “We were just growing up, learning, making nuisances of ourselves, and having a good laugh. When I saw what John became, to me he was still just the lad I used to mess about with at school.”

Inside the Merseybeat: Stories from the Scene

Tony Gaskell still plays bass guitar at 80, but his sharpest memories come from being a teenager in Liverpool at the turn of the 1960s, when skiffle was giving way to rock ’n’ roll, when The Cavern really was a damp cellar, and when Paul McCartney was just the lad up the road.

“I started playing music in 1959,” Tony said. “At 16 I was more or less full-time. I wasn’t employed as such, but I was getting paid for playing.”

Like many Liverpool kids, he began in a skiffle group. “We had a couple of guitarists who could barely play a few chords, someone made a washboard with thimbles, and I played a tea chest bass. You could never tune it properly; it just gave you a thump.” Soon enough, Radio Luxembourg was blasting Elvis Presley, Ricky Nelson and Cliff Richard into Liverpool, and the city’s teenagers were turning to rock ’n’ roll.

Tony grew up a short walk from McCartney’s house on Forthlin Road. “Paul was about 18 months older than me. In those days that was a big gap. But we knew him from the buses, from wandering round guitar shops together. Our families knew each other too. My dad was a window cleaner, and we used to do Paul’s house.”

McCartney, he remembers, was the calm one. “John Lennon was very sarcastic and acerbic, if he didn’t like you, he could cut you in half, but Paul was the opposite. He was the peacemaker. Very friendly, as you see him now.”

Tony’s own Merseybeat band, Johnny Templer and the Hi-Cats, were regulars at the city’s clubs, including the original Cavern. “It was originally about 50 yards further down. And, at that time, the whole area was a vegetable market during the day. So the roads would be covered by steel wheeled hand trucks moving through vegetables.

“And it was a real working-class scally side of town, rough as hell, and within there, they opened The Cavern. It was just a big cellar underground, a sh*thole really. No ventilation, 200 kids sweating and drooling, but it was exciting and good fun, because when you’re 16, it’s all a laugh, isn’t it?”

In the early 1960s, Merseybeat bands travelled to Hamburg, West Germany, to meet the demand for energetic rock and roll music in the Reeperbahn clubs frequented by sailors. The city offered emerging bands a valuable opportunity for performance experience and to improve their skills.

Like The Beatles, The Hi-Cats auditioned to go to Hamburg in 1961, alongside The Searchers, Billy J. Kramer and The Big Three.

Tony said: “We all passed. The promoter wanted us for Germany, but our guitarist stood up in front of everyone and said, ‘I’ve got a proper job, I’m getting engaged,’ and walked away. That was it. If we’d gone, we’d have come back like The Searchers, but it never happened.”

Even without Hamburg, Tony’s band shared bills with The Beatles countless times. “We did hundreds of shows with them. Even when they’d just released Love Me Do, we were second on the bill the night they first played it to the public. Back then they weren’t famous, just mates and musical competitors, of course. Sometimes competing over girlfriends, too,” he laughed.

He still gets a kick out of the many scrapes. There was the time his bandmates forced open a jammed dressing-room door to find Lennon mid-romance. “We lifted him off some girl and chucked the two of them out. He walked off muttering, pulling his keks up, calling us all the names under the sun.”

Or the day he tricked Japanese tourists outside McCartney’s house. “We’d found some old men’s shoes three doors down. I told the fans they were Paul’s shoes and threw them out. They went mad fighting over them. Paul’s dad came out and said, ‘You daft bugger, that fella died three days ago. And they’re size 11, Paul’s only an eight and a half!’ Somewhere in Japan there are women treasuring shoes they think belonged to Paul McCartney. And who would I be to ruin that for them?”

Looking back, Tony said none of them thought they were making history. “Every day was exciting because we were setting boundaries no one had done before. Some of us made it big, some of us didn’t. But we were all just kids playing music.”

Tony ended with a sentiment to the city he will always call home: “It’s the best city in the world; no other place can hold a candle to Liverpool.”

Forever in the ‘60s

For one Staffordshire man, the magic of the 1960s began with a single song. “The first time I heard Please Please Me by The Beatles, I was seven years old and absolutely hooked,” he said. “There was something completely and utterly different about it. Even now, it still sends shivers when I hear it.”

When Ian Mycock, 69, was growing up in the moorlands near Stoke-on-Trent, music came into the home through his mother’s collection of vinyl singles.

“We didn’t have many luxuries, but we had this radiogram, as big as a sideboard. One day that sound came out and I just couldn’t get it out of my head,” he recalled. Cliff Richard, Adam Faith and Elvis Presley filled the home, but it was The Beatles that changed everything for Ian.

Television widened his horizons with the launch of Top of the Pops in 1964. Ian soon discovered an entire wave of Liverpool talent. “You were seeing Gerry and the Pacemakers, The Searchers, The Swinging Blue Jeans… all these bands from Liverpool. It wasn’t just The Beatles. It was a whole scene,” Ian said.

By the 1970s and 80s, nostalgia tours made those artists more accessible, and Ian began meeting them in person. “They’d be in the pub before the show, just having a pint, and you could talk to them,” he said.

One vivid memory for Ian was seeing The Swinging Blue Jeans perform at his village social club in 1973, just yards from where he still lives.

Much like the atmosphere of a 60s Liverpool gig, Ian said, “These guys wanted to talk to you.” This perfectly captures the salt-of-the-earth nature of the Scousers that the Merseybeat era was known for.

And even decades later, the pull of the era remains strong. “My wife always said, ‘Why do you live in the ’60s?’ And I just say, ‘Because my friends are there, and they know me.’”